Written by Lydia Cole, Nick Harvey-Sky, Anna Kellner, Kaya Mikolajczak, Enya O’Reilly, Rosie Wright, with contributions from panellists: Herizo Andrianandrasana, Laura Braunholtz, David Kimiti, Laura Picot, and Claire Raisin.

‘Helicopter science’

In recent years, ‘helicopter science’ has crept into the lexicon of ecologists. The phrase, otherwise referred to as ‘parachute science’, is used to describe the practice whereby researchers from Minority World countries (MiW) collect data in a Majority World country (MaW), often relying heavily on local expertise and help, but do not contribute to funding or to building capacity for further research in that country, and/or sufficiently recognise the work of local collaborators or engage with the local context. (Asha de Vos and colleagues write eloquently on the subject in a Special Issue of Conservation Science and Practice.) On Monday 13th March, 2023, we – the Conservation Ecology SIG and BES Policy Team – convened a panel to have an “incredibly well-needed” discussion on the subject (as one attendee fed back). The goal of our panel was to explore inequalities and opportunities for developing ethical relationships between countries of different economic income levels, where, principally, access to money has led to imbalances of power and opportunities. In our discussion, and here, we use Majority World (i.e., the collection of nations that occupy the majority of Earth’s terrestrial surface, tending to align with the Global South) and Minority World (i.e., the Global North) descriptors to differentiate between countries, due to their greater geographical accuracy. The panel discussion was primarily designed for academics and those engaged in research, at all career stages, coming from MiW and working in or with researchers from MaW. The goal of the discussion and of this article is to enable MiW researchers to identify, design, and support ethical fieldwork. However, helicopter research is not limited to international relationships; several participants noted that that it is happening here in the UK, as well as in other national settings, and is equally important an issue to address. In this article, we have attempted to summarize some of the key points of the discussion, focusing on: (i) challenges to creating ethical research practices in field settings; and (ii) potential solutions.

Whose opinions are we representing?

Our panel comprised five people, two from MaW and three from MiW, each with unique experiences of working in international research teams:

· Herizo Andrianandrasana – Malagasy, Research Fellow at the University of Warwick

· Laura Braunholtz – British, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Stirling

· David Kimiti – Kenyan, Rangeland Ecologist

· Laura Picot – British, PhD student at University of Oxford

· Claire Raisin – British, Regional Field Programme Manager at Chester Zoo

The summary of the discussion detailed below does not acknowledge individual’s contributions, unless central to the understanding of the comment. Due to a last-minute cancellation, we didn’t manage to have equal representation on the panel. This article is principally written to inform researchers from MiW on actions they could take to redress the prominent power imbalances in international fieldwork. We are grateful to our panellists from MaW for all of their invaluable contributions to this discussion.

What’s the problem?

Failure to understand local cultures: What constitutes ethical practices when it comes to international fieldwork? Who is deciding? Generally, researchers or donors from MiW are deciding, guided by their academic interests and organisational priorities. Their interpretation of ethical may not complement or may even contradict the definition of the community in which they are working, where priorities may well differ. One panellist offered an example of how an intervention to promote gender equality within a patriarchal society led to elevated domestic violence. Challenges arise when poorly-researched ‘solutions’ are implemented. This emphasises the importance of understanding the local context, deeply, before cutting and pasting interventions that have been developed to solve superficially similar problems in a different context.

Unequal ‘collaborations’: Why are we doing our research? Who are we trying to serve through it? Researchers from MiW often imagine they know what the issues are ‘on the ground’ and how to solve them without asking the people living on that ground. MaW partners are often not involved in defining the research agenda from the start. They are the individuals managing the logistics, playing the supporting roles, whilst those from the MiW play the lead, elite roles. This is the norm. It is also the norm that MaW partners are not included in the process of paper writing; they are listed in the Acknowledgements but not given an opportunity to be a co-author, despite being key to concept development and empirical data collection, in many cases. This treatment reflects a general lack of understanding by researchers from MiW that MaW collaborators are not just field assistants. The extreme dominance of English as the language of peer-review publications, requiring individuals across nations to be able to read, write and develop ideas in what might be a second or third language, is an obvious barrier. Essentially success in academia is about getting your name on papers. Being part of a team can certainly help with the number of publications you get your name on, your citation score, but there is no metric that measures how equitable those teams you’re engaged with are. Or how well, as a leader in or member of a team you have nurtured the individuals it comprises. There are movements to describe the contributions individuals make to publications, but this attempts to address just one part of the system.

Deficient funding opportunities: The crux of it is that many funding opportunities create barriers to making research activities more ethical. Here are some examples. Funding institutions in the UK can create barriers to ethical fieldwork through making the process of paying research assistants or collaborators overseas arduous, unpredictable and delayed. They, our institutions, and ourselves, distributing funds, may also not appreciate that there are different standards in different countries, for example, local institutions may have different labour policies which can make meeting criteria for collaboration and agreeing on working protocols challenging. The availability of funding can be unequal, with many local organisations in MaW not having access to funding and/or not being able to access international funds, which favour their own citizens, e.g., National Science Foundation grants in the US fund many long-term projects in Kenya but do not allow the Principle Investigator on a project to be Kenyan, creating an imbalance that can have implications for career development. Research projects typically span a period that falls far short of the length of a career, with contracts for field assistants routinely extending for just a number of months across a ‘field season’, for up to a maximum of two-three years. The end of a project often leads to an economic vacuum in MaW localities. Early career researchers (ECRs), notably PhD students who are frequently the ones organising and carrying out data collection exercises, eager to develop ethical approaches to international fieldwork, such as through providing collaborators with more resources, are reporting limited funding opportunities to support them to do that. All of these issues can have reverberations for career development amongst MaW collaborators.

Poor communication & infrastructure: The lack of effective communication can have a huge impact on the fulfilment of more ethical approaches. For example, prior informed consent forms may be difficult to understand for some participants from MaW, whether due to language or unfamiliarity with extra-local procedures. Communication with MaW collaborators via the internet can be challenging in locations with poor internet access and/or electricity availability, for example some rural parts of Madagascar have no connection to the grid and rolling power cuts are occasionally implemented by the national electricity utility. Even if communication via the internet is available, the opportunities the internet provides may be limited, for example access to academic publications can be restricted, with many journals having a pay-wall that institutions from the MaW cannot afford. When it comes to feeding back results of research, the style of communication can often be inappropriate for the target audience, i.e., English language used amongst an audience who cannot understand it, deeming dissemination of results ineffective. In some cases, the ‘target’ audience – for whom research findings might be most beneficial – is also mis-identified, alongside choosing an inappropriate medium for communicating results. In summary, MiW researchers rarely effectively communicate results to those who have helped collect the data, or whom the data is about.

What’s the solution?

Read and follow the Code of Conduct for Ethical Fieldwork! The Code provides guidance on how you can engage with and address key challenges associated with different aspects of fieldwork. We encourage you to share the Code amongst your colleagues and communities, especially the ‘bad actors’. Adopting the Code is then the essential step towards driving change.

Collaborate with your collaborators: In parallel with the first action, explicitly ask your MaW colleagues what they need in order to collaborate in an equitable way. What are the particular challenges they face in their work, or in their career development? What aspirations do they have from this project? Working in any collaboration also opens up opportunities for capacity sharing. What can you learn from your collaborators, and what can they learn from you? Take time to listen to the answers. Consider also who is managing and who is being managed in your project. Are local collaborators given the same opportunity to fill management roles as international ones? Or are MaW collaborators assigned only to data collection? If the latter is true, is that distribution of labour and hierarchy justified? Question the power dynamics at play and/or pre-empt imbalances between collaborators such that they can be addressed at project inception. There need to be opportunities for researchers from MaW to be Principal Investigators (PIs) on grants. We need to address the funding-related, logistical, institutional and individual biases that create a ‘ceiling’ for capacity building and capacity sharing.

Provide funding opportunities: The principles and supply of project funding can have profound implications and demonstrate the values of an institution. The Code of Conduct for Ethical Fieldwork resulted from the University of Oxford putting their money where their mouth is, when asked by an activist graduate student collective for departmental funding to develop fieldwork guidance. The Code covers all stages of a research project; funding must also. When embarking on a new project, consider how finances can be secured to enable the entire process of a research project to be co-written between international collaborators, from writing the full funding application to completing the final research report, two parts of the process that can easily lack a collaborative element. There needs to be more emphasis on ‘scoping’ a situation and building relationships before funding is awarded, and in a way that enables research to be community-led, addressing their questions, rather than questions pre-conceived by remote researchers. This approach will increase the likelihood of the project being successful in terms of addressing community needs. New models of funding may be needed to support true collaboration from the very start, where review panels consider ‘due diligence’ in their decisions over which projects to fund, for example, they assess whether local communities, local researchers, or local governments are aware of the MiW researchers’ plans and the research questions being (im)posed on the locality. True collaboration also relies on there being sufficient funding opportunities to support MaW researchers. In many locations, funding opportunities local to MaW researchers can be entirely absent, meaning individuals have to look to international institutions, which often prioritise supporting their own. If a funder does not appear to be providing opportunities for funding international collaborators, ask them why and how they could be doing more to support them. Advocacy could again be effective in encouraging better policies within funding organisations, around due diligence assessments, parameters of funding offered, etc.. Chester Zoo, for example, has a principle whereby for every new MiW PhD studentship working in Madagascar, a local Malagasy student has to be funded also. When you are applying for funding for a project, try to budget sufficiently for the time and work of the whole team. Some funding bodies are realising the importance of this shift in financial support for field teams, rather than individuals. Another shift required by funding bodies is to allow for equipment purchased for a project to be left in the ‘field’, rather than having a requirement that it must be brought back from the field post data collection, potentially restricting local collaborators from developing expertise and having the capacity for long-term data collection.

Providing opportunities beyond financial: Researchers from MiW, especially those in their early career, often encounter requests for help by local participants/collaborators from MaW. Financial help is often impossible or inappropriate but consider if there are other ways you can help. Ask your collaborators what their next steps are and how you could support them. Mentoring is a free way of providing support to colleagues from MaW; advising and guiding early-career collaborators, providing feedback on written work, and introducing them to different organisations (locally or internationally), can be invaluable for building confidence, capacity and networks. Factoring in more time for international collaborations will create opportunities for in-kind support and capacity sharing, valuable at all career stages. Taking a long-term perspective in developing relationships with collaborators and communities is also key when funds can be transient. Most projects come to an end all too soon, leaving MaW collaborators within an economic vacuum. The drying up of, often, international project-related funds can cause local individuals, and their families and communities, to be without income. To overcome this, try to develop close relationships with individuals and institutions that will last beyond projects, to facilitate building resilience for all parties. One panellist succinctly summarised this point: “Don’t try and work with everyone everywhere, work with one or two people really closely.” The Wildlife Conservation undergraduate and Masters programmes at the University of The West of England (UWE Bristol), for example, has established close relationships in Madagascar over time: with an NGO, SABADE, with communities in one locality, and with the University of Antananarivo, facilitating capacity sharing between all parties during regular student fieldtrips to the country.

Effective communication: It is vital to consider carefully how you can most effectively communicate and transfer knowledge across cultures and countries. It is important that all collaborators know, for example, how long a project may generate employment for, and vitally, for them to be able to discuss this and every aspect of the project. It is also important to maintain communication with the communities you work with throughout and after the project, and to feed results back to them in accessible ways, without creating an extra burden for local partners.

Training: One very important topic (that we barely touched on in the discussion) is training needs of PhD students and ECRs to support them in planning and completing international fieldwork in an ethical way, with limited time, financial resources, and often confidence. Guidance may also be valuable for PhD students and ECRs on how to talk to their supervisors or more senior colleagues, accustomed to performing helicopter research, or for undergraduates, being taken on fieldtrips where unethical practices are engrained. Training should also be designed for supervisors of PhD students and individuals at later career stages, with more power and resources available to them, to encourage them to engage with these issues more deeply and to support ECRs to drive change. A single PhD student or ECR should not be asked to tackle the systemic challenge of inequality on their own. As well as targeted training in MiW institutions, consider how you can incorporate training into the research project, for the whole group. A whole-group training course at the start of a new project on how to achieve meaningful/’real’ co-production, for example, may be hugely beneficial. This training should consider all of the skills required to be successful in research/academia, from data collection to writing journal articles or policy-facing summaries, taking into consideration the differing, specific needs of MaW vs. MiW collaborators. MaW collaborators, for example, could benefit from support to develop institutional policy to “tighten loopholes on unethical fieldwork”.

Consider your role in driving change: What can you do as an individual to make fieldwork practices more ethical? What change depends on action from your institution? If the latter is the case, can you lobby them to change institutional policy? We all have a voice. Student activism can be very effective, as proved the case with the provision of funding for the development of the University of Oxford’s Code of Conduct, a key document that is guiding institutional, and thus individual change. Advocacy at any career stage is an option available to us all. But we all have different restrictions on our time and resources; we have to pick our own battles. And to look after ourselves, and look out for others. Finally, as David shared: “tyranny is the removal of nuance”. Any ecologist will know that no one-size-fits-all. Every ecosystem is different. The same applies to communities, of course, and in each place or project that we work, we must allocate sufficient time and space to deeply engage with it.

Final remarks

We have just scratched the surface of ‘helicopter science’ in this article, and in the panel discussion that generated it. We hope that this summary has given you some points to consider when you next plan fieldwork, a project, or reflect on work going on elsewhere. One of the key solutions offered by panellists was to “stay engaged”: to ask questions about the plans and practices that you see, talk to colleagues, consider how things could be done differently. This is easier said than done when you are confronting engrained practices and intransigent colleagues, especially when you’re at an early career stage.

It was evident as the discussion developed that exploring ethical fieldwork was really just a guise to exploring the much broader issue of global inequities and the challenges of academia as a system designed for knowledge creation and sharing. The latter goal is as important as the former, as is the diversity of minds generating that knowledge. Although many of the challenges discussed in this article are symptoms of the system in which we function, often feeling beyond our scope of influence, that system is made up of us – individuals – and that is where awareness and change must start.

What next?

The feedback we gratefully received from participants confirmed our suspicions when we were organising the event: we tried to cover too much in too little time. And importantly (and in contradiction to the theme of the event), there was feedback that we didn’t give enough time to listen to our panellists from MaW talking about the scale and nature of the problem and their thoughts on how we can prevent helicopter science from happening in the first place. We’ve noted all of the feedback and look forward to trying again at our next event (watch this space for a longer, interactive, discussion-focused workshop at this year’s Annual Meeting).

Resources from the event:

Andrianandrasana, H. T., Savage, J., Volahy, A. T., Long, P. R., & Jones, N. (2022). Participatory Ecological Monitoring (PEM): Participatory research methods for sustainability‐toolkit# 4. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 31(4), 231-233. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.31.4.7

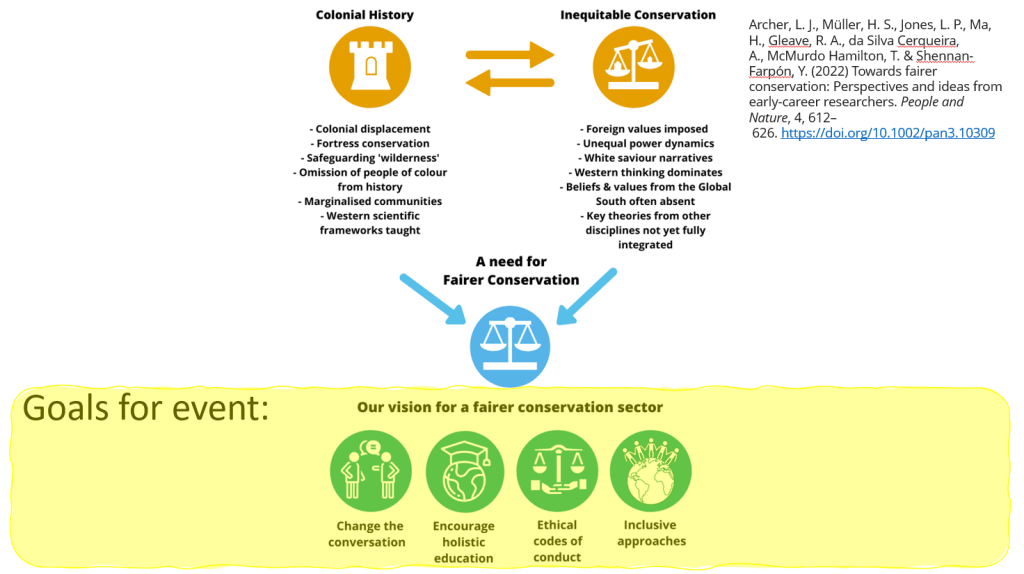

Archer, L. J., Müller, H. S., Jones, L. P., Ma, H., Gleave, R. A., da Silva Cerqueira, A., … & Shennan‐Farpón, Y. (2022). Towards fairer conservation: Perspectives and ideas from early‐career researchers. People and Nature, 4(3), 612-626. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10309

Ocampo-Ariza, C., Toledo-Hernández, M., Librán-Embid, F., Armenteras, D., Vansynghel, J., Raveloaritiana, E., … & Maas, B. (2023). Global South leadership towards inclusive tropical ecology and conservation. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2023.01.002

Picot, L. E., & Grasham, C. F. (2022). Fieldwork: institutions can make it more ethical. Nature, 609(7926). https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-02805-6

Picot, L. E. and Grasham, C. F. (2022). Code of Conduct for Ethical Fieldwork. University of Oxford. DOI: 10.5287/bodleian:GOkXB2Pye