By Jessica J. Coldrey and Benjamin S. Thompson.

This Plain Language summary is published in advance of the paper discussed; check back soon for a link to the full paper.

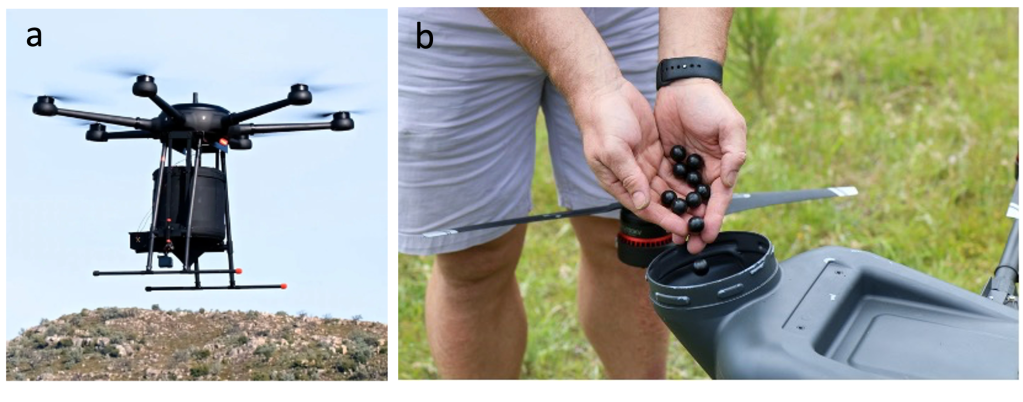

Forest restoration efforts are becoming more common around the world. These projects can help reduce the impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss. Planting seeds and seedlings by hand can be slow, physically intense, and limited to safe, accessible areas. However, with new technologies available, some companies are developing and using seed-dropping drones. People load the drones with seeds or seed balls, and an on-ground pilot helps fly the drone over land to disperse the seeds. Although some suggest this is a faster way to plant trees, questions remain about people’s feelings and perceptions about drones. Flying regulations, technological limits, and seed germination rates also determine how much drones can help the environment.

Our research asked how drones can contribute to global restoration efforts and what contexts they best suit. We interviewed people involved in drone-led forest restoration in Australia, including people developing and using the technology, purchasing these services for their land, and others working in or researching restoration. This approach helped us understand the challenges and opportunities of drones in the forest restoration industry, now and in the future.

Opportunities included using drones to drop seeds on land that is difficult or unsafe to access on foot, such as following bushfires, floods, or landslides. They were also considered helpful in restoring land between 20-100 hectares in size. Drones may also help ease the labour shortage of professional restoration ecologists and tree planters in Australia. However, challenges with using these drones included regulations restricting where and when people can fly them, the unproven ability of drones to control weeds, and the uncertain supply, germination, and survival rates of the seeds that drones drop.

By analysing forest systems and combining this with interview information, our findings can help restoration managers identify suitable sites for drone-led restoration. It may also allow policymakers to review regulations that limit drone use. We conclude that drones are currently a ’boutique’ tool that supports, rather than replaces, existing restoration approaches.