By Bauld, J., Coad, L., Whytock, R. C., Midoko Iponga, D., Babicka, M., Pambo, S., Loundou, P., Ingram, D. J. , Jeffrey, K., Bessone, M., Wilkie, D. S., Starkey, M., Ngama, S., Cornelis, D., and Abernethy, K. A.

This Plain Language Summary is published in advance of the paper discussed. Please check back soon for a link to the full paper.

In tropical countries, people consume meat harvested from wildlife (“wild meat”). However, growing human populations mean wild meat demand often drives unsustainable hunting, threatening wildlife populations and people reliant on wild meat for food and livelihoods. To design effective interventions, it is crucial to understand who consumes wild meat, who eats alternatives, and what influences these choices.

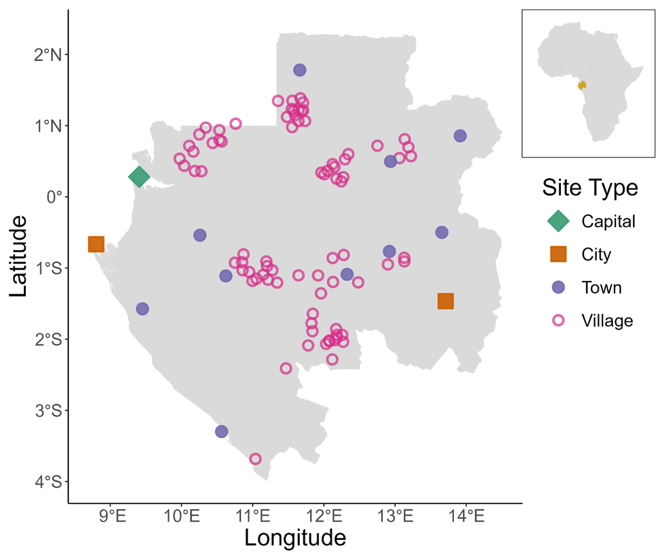

In our study we used the WILDMEAT database, which has combined data from many past studies of wild and alternative meat consumption in Gabon, to undertake a national-scale analysis of factors shaping household meat consumption. We found that households in small, isolated villages were most likely to consume wild meat, or no meat, in the previous day, and were most likely to obtain wild meat or fish via hunting and fishing. As settlements became larger, the likelihood of wild or no meat consumption fell, and consumption of livestock, poultry, and fish increased. Households were also more likely to buy meat, rather than hunt or fish, in larger settlements and less isolated villages. Prices also influenced consumption, with consumption of all meat types becoming less likely as prices rose, with one exception. Commercial fish products, as opposed to those caught locally, were consumed more in villages when prices were higher. This positive relationship between price and consumption suggests that commercial fish products, mostly tinned fish, could be an essential good to village households, as they may be the only alternative available if a household does not successfully hunt or fish.

Our results suggest three categories of households. Firstly, isolated households reliant on subsistence hunting of wild meat, who cannot easily lower consumption due to few alternatives. Secondly, households in small towns or less isolated villages that buy some of the wild meat they consume. Here, increasing the availability and affordability of alternatives, such as locally farmed fish, may encourage more frequent purchasing of wild meat alternatives. Finally, urban households who purchase most of the wild meat they consume and can already access alternatives. Here, demand reduction through persuasive messaging may encourage consumers to more often choose wild meat alternatives.