By Syamili Manoj Santhi, Tuomo Takalaa, Aino Korrensalo, Nataša Lovric, Jukka Tikkanen, and Eeva-Stiina Tuittila

The human-forest relationship rooted in evolutionary significance has evolved over millennia. During the coronavirus pandemic, the human-forest relationship—once one of distance due to industrialisation—acquired new meanings. People increasingly turned to natural environments such as forests for comfort, stress relief, a sense of peace and overall well-being. As a result, most research has largely focussed on public forest preferences and health benefits associated with forest exposure. The values people attach to forests and the subjective emotional experiences through which forests enhance overall well-being have received far less attention. In this study, we’re diving into how people experience joy, meaning, and emotional well-being through their connection with forests, to develop a new ‘Forest Happiness’ concept.

We chose Finland as our focus area, and for a good reason. Finland isn’t just one of the most forest-rich countries in Europe. It has also been named the happiest country in the world for eight years in a row. With a deep-rooted forest tradition, Finland provides the perfect setting to explore how forests contribute to happiness in everyday life. To do this, we conducted a national, multilingual survey (available in Finnish, Swedish, and English) to understand how Finns conceptualise forest happiness. Happiness is approached as a subjective concept spanning from transient joyful experiences to deeper forms of fulfilment.

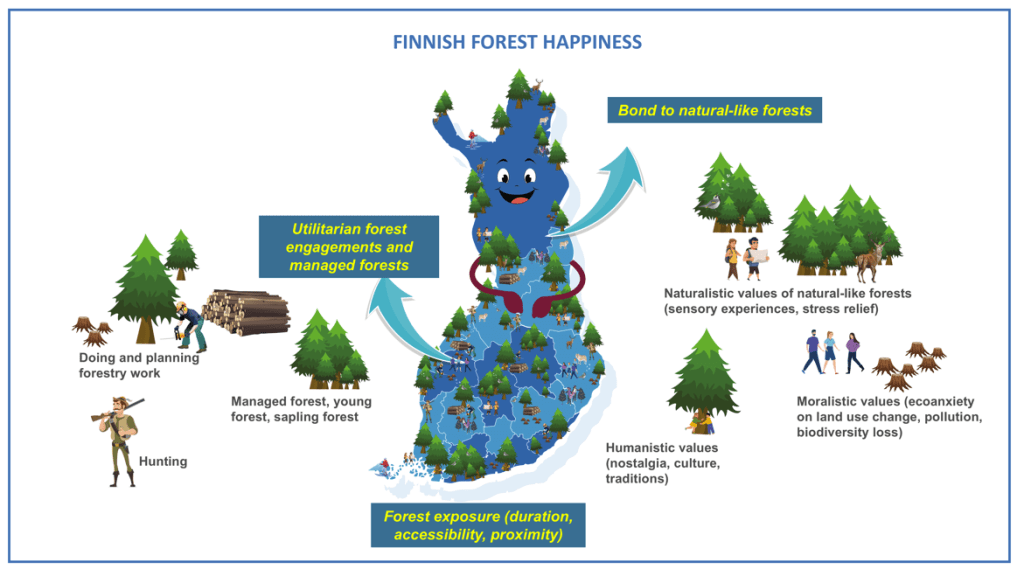

Most people in our survey said that their lives would be considerably unhappier without their relationship with forests. In Finland, forest happiness seems to come from three main sources: (1) a deep bond with natural like forests; (2) practical activities commonly done in managed forests; and (3) forest exposure. Natural elements of forest brought a deeper sense of happiness through sensory experiences, and through Finnish cultural values that emphasise silence, personal space, solitude and spiritual reflection. On the other hand, active forest interactions such as picking berries, making firewood, managing the forest and planning forest operations boosted both fleeting happiness and deep feelings of fulfilment. Among Finns, these activities hold deep cultural significance, passed down through generations. Beyond these findings on the cultural context, childhood living environment, access and familiarity to different types of forests all come together to shape the way people experience forests and influence which aspects of those experiences contribute most to their forest happiness. At the same time, damage and degradation to natural-like forests due to clearcutting, pollution, biodiversity loss and land-use change, reduced people’s perceived happiness, leading to eco-anxiety.

Our study reflects a wider societal tension between the conservation of remaining natural-like forests and potential forest utilization among Finns. It supports calls for forest-related policies and city planning to consider how people value different types of forests, thereby recognising and balancing this diverse valuation rather than treating all forests as the same. Finally, for forest-based therapies to truly support happiness and well-being, they should be tailored to match people’s personal forest experiences and preferences.