By Kate Pratt and Vishnu Prahalad

As people become increasingly disconnected from nature, conservation efforts face a growing challenge—people are unlikely to protect what they do not understand or value. This is particularly concerning for wetlands, one of the most essential yet most threatened ecosystems on the planet. Wetlands provide critical habitat for countless species, act as natural water filters, and serve as buffers against floods and climate change. However, urbanisation, pollution, and habitat destruction continue to degrade these vital landscapes, often with little public outcry compared with other ecosystems like forests and beaches. Without direct experiences that foster appreciation—such as walking through marshes, birdwatching, or learning about wetland biodiversity—many people remain unaware of their importance. Reconnecting people with nature, particularly through education and immersive experiences, is crucial to ensuring the survival of these irreplaceable ecosystems.

Before we can effectively reconnect people with wetlands, we first need to understand how they interact with these ecosystems in the first place. This means exploring what draws people to wetlands, what they enjoy about them, and what barriers might prevent deeper and wider engagement. Do people appreciate wetlands for their wildlife, tranquillity, or recreational opportunities? Are they deterred by perceptions of wetlands as boring or inaccessible? Understanding these attitudes, along with the activities people currently engage in, is essential for developing meaningful conservation strategies. By identifying what fosters a positive connection, and what hinders it, we can create experiences that encourage people to value, protect, and advocate for these vital landscapes.

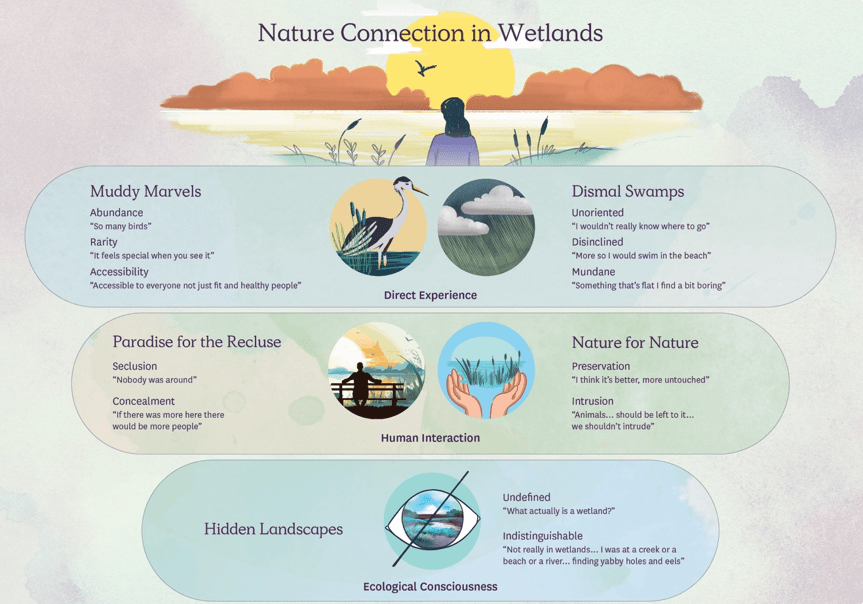

To understand how individuals currently connect with wetlands, we conducted on-site semi-structured interviews with 62 participants across 14 diverse wetlands in Tasmania, Australia’s southern island state. Analysis of these interviews revealed five key themes and twelve subthemes, which were structured into three levels based on their relationships (Figure 1). The results highlighted visitors’ direct experiences with wetlands, both positive (“Muddy Marvels”) and negative (“Dismal Swamps”), as well as their interactions with other visitors (“Paradise for the Recluse”). Participants also shared their perspectives on potential wetland development (“Nature for Nature”) and how wetlands fit into their broader worldview (“Hidden Landscapes”). These findings expose the complexity of people’s relationships with wetlands, revealing both appreciation and aversion. To foster stronger connections and encourage conservation support, it is essential to address these diverse perceptions. Recommendations include making information on wetlands more accessible, tailoring experiences to visitor preferences, creating immersive and transformative opportunities, and cultivating a cultural identity around wetlands that enhances their visibility and significance. By integrating these insights into policy and practice, we can create meaningful experiences that inspire people to value and protect wetlands.