By Maraja Riechers, Tamara Schaal-Lagodzinski, Laura M. Pereira, Jacqueline Loos, and Joern Fischer

Many of today’s challenges—such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and inequality—are deeply embedded in complex systems that are difficult to change. Our research introduces a new approach to better understand and guide sustainability transformations: the ‘chains of leverage’ framework.

Because social-ecological systems are highly interconnected and constantly adapting, interventions can have unintended consequences. A small change in one part of the system may trigger a chain reaction, affecting other areas in unpredictable ways. Also, knowing where to intervene in a system is a very challenging endeavour. To navigate this complexity, our framework helps identify how changes at different levels of a system reinforce or conflict with each other, offering a roadmap for more effective interventions.

How ‘Chains of Leverage’ Work

The framework follows four key steps:

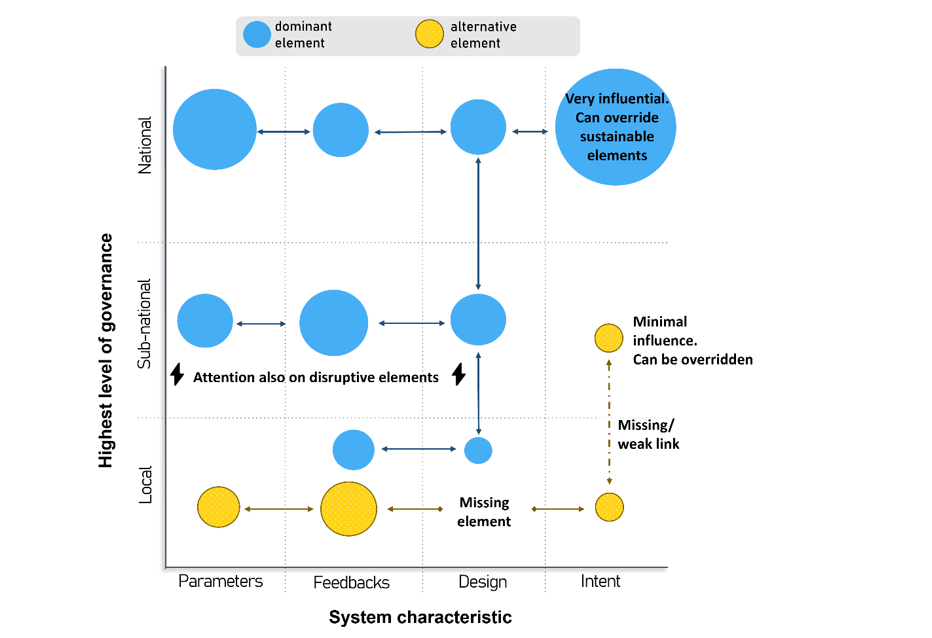

- Understand the system’s core elements – Every system consists of different components, from surface-level rules and policies (parameters) to deeper structures like institutions (design) and underlying worldviews (intent).

- Examine interactions and relationships – Changes at one level can trigger shifts in others. For example, new policies might strengthen or challenge existing social values, creating a ripple effect through the system.

- Identify ‘chains of leverage’ – By mapping out how these elements interact, we can see whether changes work together (reinforcing sustainability) or against each other (creating obstacles). This includes examining power dynamics and governance structures, which shape how and where change happens.

- Prioritise key interventions – Instead of relying on small, isolated changes, we pinpoint the most strategic leverage points where action can have the greatest impact. This could include: (i) strengthening sustainable elements already in place, (ii) dismantling influential but unsustainable elements, (iii) reducing mismatches or inefficiencies in the system to create a sustainable chain of leverage.

The ‘chains of leverage’ framework helps decision-makers and researchers make smarter choices about how to shift systems toward sustainability. It highlights not just where to act, but how different actions interact, making it easier to avoid unintended consequences like policy resistance or rebound effects. Ultimately, this approach moves us beyond incremental change toward coordinated action that can create lasting and meaningful sustainability transformations.