By Laura Tensen and Peter Teske

Many researchers believe others have excluded them from academic discourse at some point int their careers. Female scientists may feel that male scientists discriminated against them because males have historically dominated STEM, and researchers from low-income countries may feel that they cannot compete against researchers from resource-rich institutions in North America, Europe and East Asia. Despite its potentially destructive effect on careers and the advancement of science, the prevalence of academic exclusion has received surprisingly little attention.

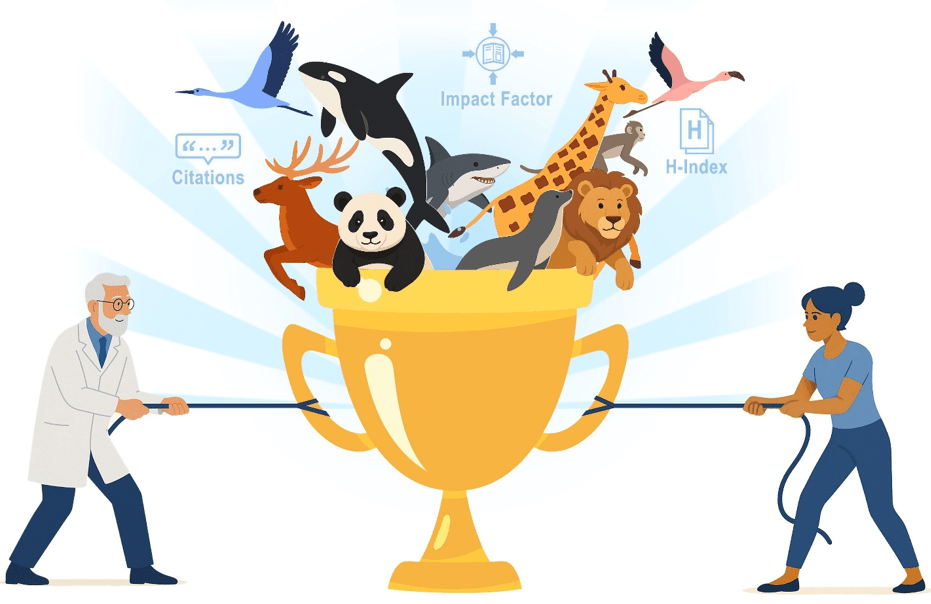

In this study, we explored a type of academic exclusion that is unique to the biological sciences: research monopolization of study species, where established researchers try to prevent potential competitors from studying their preferred animal or plant. We hypothesized that this would be of particular concern when it comes to ‘charismatic’ species, such as the big cats, whales, sharks, penguins, and the great apes.

We found a positive correlation between a species’ charisma and the impact and volume of scientific outputs, clearly highlighting the benefits of studying such species on a researcher’s prestige and career prospects. This was coupled with a greater number of international collaborations, with a strong bias towards researchers from low-income countries in Africa, Southeast Asia and South America (to which most of the charismatic species are native) participating in research that scientists from well-funded elite universities led. Nonetheless, studying charismatic species tended to increase the likelihood of negative workplace experiences. To illustrate, 46% of respondents encountered research monopolization, and they expressed particular concern about other scientists refusing to collaborate and stealing research ideas or intellectual outputs. Particularly female and less experienced scientists often reported that other scientists have prevented them from studying their species of choice, forcing them to change their original research trajectories. Race and country of origin also played a role.

Our study confirms that research monopolization is a problem in the biological sciences, and that the choice of study species strongly influences monopolization. Awareness of such unethical behaviors may be a first step in helping to ensure more equitable opportunities for all researchers in the field.