By Julian Clark, Jim McGinlay, Nikoleta Jones, and Victoria A. Maguire-Rajpaul.

Understanding how humans interact with and make decisions about landscapes is crucial in addressing pressing global challenges like climate change and sea level rise. This research introduces the groundbreaking concept of “landscape-as-governance” (LAG), which redefines how we understand human interactions with landscapes by integrating sensory experiences and governance preferences. LAG bridges two previously unconnected fields—enactive cognition and polycentric governance—to reveal how sensory experiences and sensemaking processes co-constitute human agency in landscapes. This interdisciplinary approach challenges mainstream social-ecological systems (SES) thinking by moving beyond human-centred agency to recognize the intertwined and co-constituted nature of human and ecological interactions.

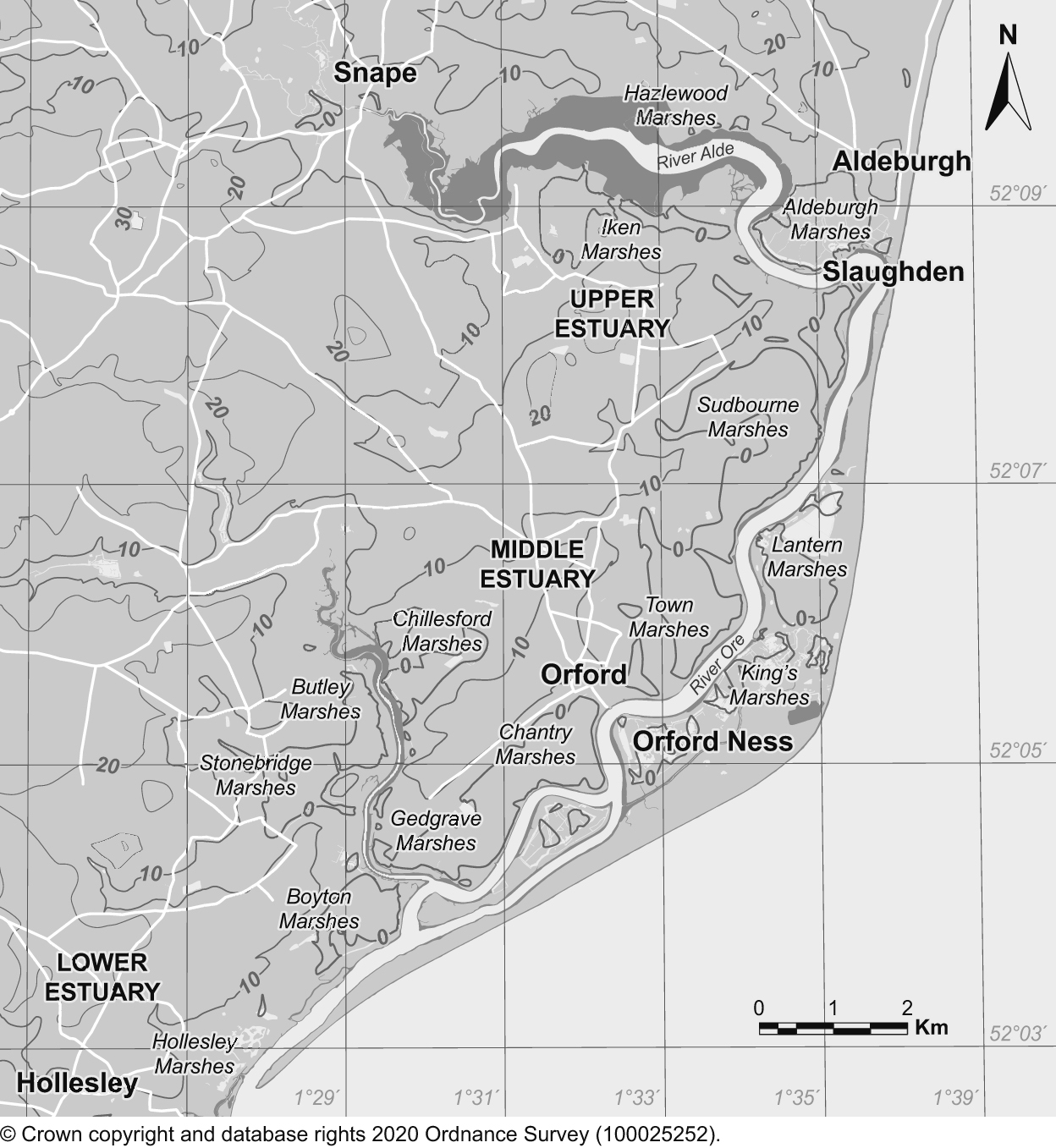

The specific research question is: How do individuals’ embodied sensing and communities’ collective sensemaking of landscapes influence their preferences for landscape governance? The study focuses on the Alde and Ore estuary in east England, a landscape at the frontline of climate change, to explore how sensory experiences intersect with power dynamics and governance structures to shape decision-making about its management. We conducted 20 semi-structured interviews with long-term residents including sensing walks guided by them, participant observation, and archival research. These methods allowed the team to explore how people’s sensory experiences of the estuary landscape informed their preferences for its management. Data analysis involved pattern matching with documentary sources and applying polycentric governance theory to understand decision-making processes and power relations. The study provides unique insights into the emotional and sensory dimensions of governance, which are often overlooked.

The findings revealed three key insights:

(1) Embodied sensing shapes governance preferences.

People’s sensory experiences of landscapes—such as the feel of wind, the sight of tidal flows, and the sound of migratory birds—profoundly influence their emotional connections and decision-making preferences. What we feel concerning landscapes shapes what we decide about them. Recognizing the role of embodied sensing can help policymakers design more inclusive governance strategies that account for diverse emotional and sensory connections to landscapes. For example, community consultations could incorporate sensory-based methods like walking interviews to better understand local governing preferences.

(2) Human agency in landscapes is co-constituted. Our governance preferences for specific landscapes are not solely driven by our cognition, but emerge from our sensory relationship with these social-ecological systems. This co-constituted agency evolves over time through sensory experiences, historical interactions, and embedded norms. Policymakers and community leaders can use this insight to promote bottom-up innovation and adaptive governance approaches that reflect this dynamic interplay between people and landscapes. For example, integrating historical and ecological narratives into current decision-making can foster more sustainable and equitable landscape policies.

(3) Power dynamics are embedded in landscape governance. What we describe as “preservationist” preferences often dominate landscape management due to entrenched power relations and privileged access to landscape decision centres that have built up over time, while more “transformative” approaches struggle to gain traction due to public fear of landscape change and uncertainty over how to chart transition pathways. Policymakers can address these issues by creating platforms for marginalized voices and fostering deliberative processes that explore alternative governance strategies. For instance, community workshops could visualize transformative scenarios to reduce anxieties over change and build support for adaptive strategies such as managed realignment of coasts.

This research highlights the importance of understanding the sensory and emotional dimensions of landscape governance. By introducing LAG, it opens new research frontiers in SES studies and provides actionable insights for addressing climate change and fostering adaptive management.