By Sophie Caillon, Jonathan Locqueville, Doyle McKey, Kenneth MacDonald, and Sylvain Coq.

Recent research on human interactions with nature has focused on reciprocal relations. Reciprocal relations are those that involve two-way influence between humans and non-human nature, and are typically expressed through empathy, trust, collaboration, and mutual aid. An alternative to reciprocal relations is instrumental values. They focus on the functionalities of an ecosystem or on the services humans can extract from the ecosystem. But instrumental values do not capture the complexity, non-explicit and non-materialistic relations between humans and nature.

Research on relational values and reciprocal interactions with nature has mostly been conducted with indigenous and local communities. Specifically, small-scale and subsistence harvesting is generally thought to have less of an effect on nature and to respond to more sensitive and relational values than professional commercial harvesting. This perception may explain why there is less research on relational values in the commercial harvesting of plants for use by the manufacturers of cosmetic or medicinal products, and even less research on professional harvesters living in high-income countries. Historically these relations have been seen as largely extractive, generally supposed to be driven primarily by the need for profitability, and not based on either an ethic of care for non-human beings, or the management of these plants.

Here, we study how resource management practices led by professional harvesters do or do not incorporate the reciprocal values and interests of other, human and non-human, actors. We interviewed professional harvesters who collect Arnica, a widely used wild medicinal and aromatic plant, in the Massif Central of France and sell it, through cooperatives, to manufacturers of health and cosmetic products. We spent time with harvesters in their collection sites and with farmers who own some of those sites, and attended meetings organised by local institutions that aimed to develop resource management plans for protecting the area and in which harvesters played important roles. We also interviewed managers of manufacturing firms.

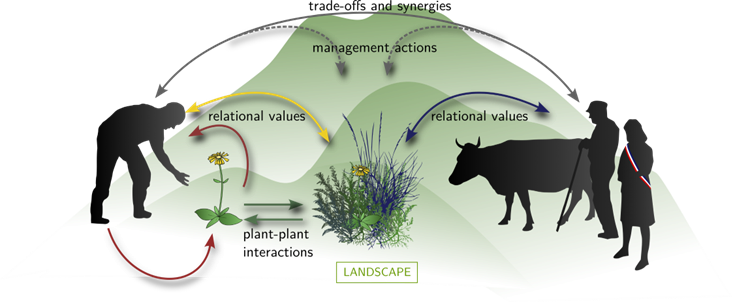

The research revealed that while Arnica harvesters only visit their sites infrequently, they accurately observe conditions that are favourable to arnica production and understand that their long-term interests require healthy ecological relationships and management practices in their harvesting sites. They recognize how Arnica responds to other plants and to human interventions. To favour Arnica regeneration and assure right of access to the resource, they engage in reciprocal relations with other harvesters, farmers, managers of protected areas, land owners and elected representatives in charge of the territory. This has led Arnica harvesters to become involved in developing policy and plans for landscape and natural resource management. These plans promote sustainable landscapes in general rather than practices that benefit a particular plant. This can be seen as a form of reciprocity in which harvesters compromise immediate benefits in support of management programs and ecological relations that produce ecologically healthy Arnica sites in the long term. At the same time, Arnica and associated species benefit from the interest, observations and actions of professional harvesters.

We conclude that professional Arnica harvesters hold relational values that underpin reciprocal relations with nature. More research with professional harvesters in other regions and with other species should be conducted to develop a greater understanding of the extent to which relational values exist in other harvesting contexts.