A blog post about the paper ‘Servicesheds connect people to the landscapes upon which they depend’ by Yiyi Zhang, Hugo Thierry, Lara Cornejo, Lael Parrott, Monique Poulin, Kate Sherren, Danika Van Proosdij, and Brian Robinson, first published: 05 December 2024, written by Brendan Fisher, the Associate Editor who handled the paper.

Read the full paper here.

The local pub, the home team, biking distance, the mom-and-pop shop, all these terms connote an image, maybe an ideal, of something close by, something connecting us to our community, our landscape, our closest beer or wine. The term ecosystem serviceshed has not quite reached the level of digestible understanding as these other terms, but… ok…its nowhere near as fluent or known, but thanks to work like the recent People and Nature publication by Zhang et al (2024) “Servicesheds connect people to the landscapes upon which they depend” we might be getting a bit closer.

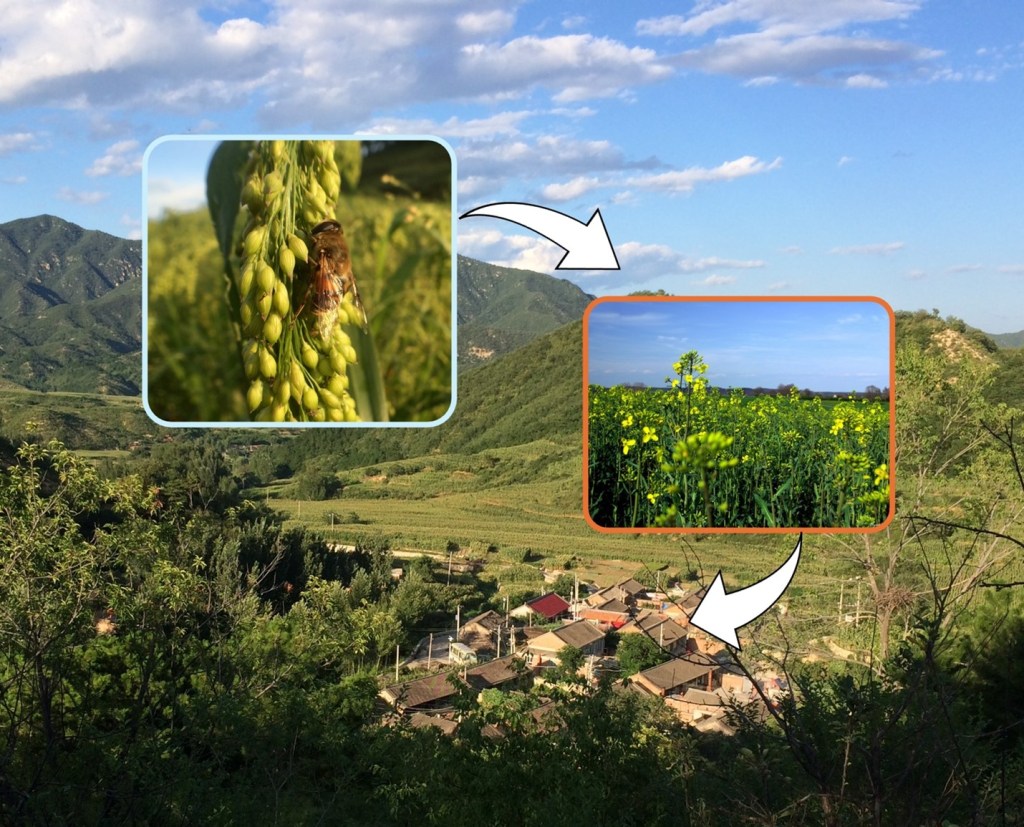

In their paper, Zhang et al. (2024) connect provisioning and regulating ecosystem services generated in coastal and agricultural regions in eastern Canada with the fishing and farming beneficiaries of these services. Through a suite of mapping and modeling exercises the authors demonstrate an approach and provide empirical results that explicitly connect people to the landscapes providing the critical ecosystem services they enjoy and rely on – from food and fish production to pollination and flood control.

In their study areas, we find out that 2/3 of pollinator habitat co-exists with the agricultural lands that the pollinators service, and about a quarter of the flood-regulating coastal salt marshes co-occur where their flood-prone communities sit. Their work takes ecosystem service research to a landscape scale and forces one to account for processes at a meso-scale, a scale that can be managed, a scale for which policies can be derived or improved.

So, while ecosystem serviceshed maybe not be as fluent a concept as downtown, or upriver yet, the concept does force the reader to think of connections between nature that provides services and those of us who benefit from them. It connects us in a spatial and temporal way, at scales we implicitly understand and care about.

Throughout the 1990’s the term biodiversity was constantly catching people up on its newness and what it actually meant (see Feb 23, 1997 NY Times “Coining a Catchword). And while it is arguable that it is still used incorrectly in the popular domain, it has become a term that most people at least think they understand. If, in twenty years, people are throwing the term ecosystem serviceshed around as they bike to the local pub to watch their home team on the television, it’ll be thanks to research like Zhang et al (2024)* for clearly demonstrating the usefulness of it.

*It looks like Mandle et al (2015) was the first use of the term in the published literature, and Tallis et al. (2012) in the grey literature. We should thank them too.