By Siyu Qin, Ana Buchadas, Patrick Meyfroidt, Yifan He, Arash Ghoddousi, Florian Pötzschner, Matthias Baumann, and Tobias Kuemmerle.

In many tropical regions, forests have been shrinking; conservation areas have been expanding, and international funding has been increasing. How have these three trends interacted with each other over time and across space in the major deforestation regions of South America?

One way to look at the interaction between decreasing forest cover, increasing conservation areas, and increasing funding is to see conservation efforts as responses to expanding deforestation, and from this angle, we may ask whether conservation actors allocate more funding to areas with high remaining forest to secure, or to target areas with high deforestation rate to slow it down. Another way to look at it is that conservation funding is also a type of investment in lands worthy of protecting. From this angle, we may ask whether money goes to areas already conserved or to areas we’ve already spent more money on.

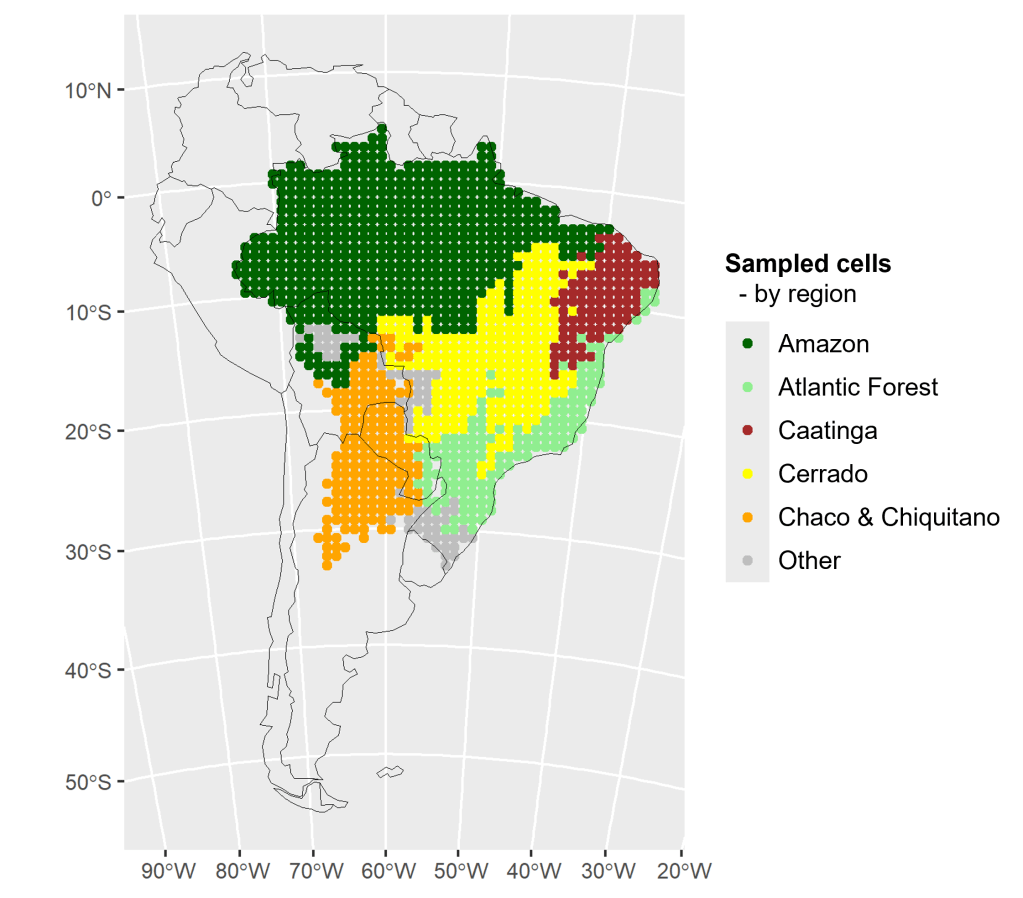

We tested these assumptions with spatial data of 30 years of forest cover, conservation areas, and international conservation funding in the forest and savanna biomes of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay. It turns out that money tends to go to places that are already recognized for conservation, like national parks and other conserved areas including Indigenous territories in Brazil, and to areas that have received funding before. This shows that areas recognized as contributing to conservation can be key in attracting financial support to faciliate their delivery of conservation outcomes.

Interestingly, our impression that we spend more money when there’s more deforestation is both right and wrong. As we see less and less forest over the 30 years, we are indeed spending more money. However, when donors decided to give the money, this money did not necessarily go to the specific places that are going through rapid deforestation but to areas with a lot of remaining forest. So eventually we are seeing more and more money concentrated in gradually shrinking areas with remaining rainforests – such as the Amazon.

Whether money goes to areas with more forest or more deforestation also depends highly on the scale and context. While money generally goes to places with more forests rather than the fastest deforestation, if we look within each regions, it is not the case. Within each region, money doesn’t care that much about how much forest is in a place, but slightly more about how fast the forest is disappearing. In some regions, conservation money went to places with more rapid deforestation, and in some, money avoided those places. To make sure our conservation efforts are fair and effective, we need to better understand these patterns.

As organizations and governments promise to fund conservation and protect more of our planet, our study can support them to ensure that the money are better distributed to help the forests in need and the lives they support.