In celebration of the shortlisted papers for the Rachel Carson Prize 2023 for Early Career Ecologists, we’re delighted to introduce you to some of our shortlisted individuals and papers.

The many shades of the green city – pluralizing the meaning of the urban nature.

About the paper:

What is your shortlisted paper about and what are you seeking to answer with your research?

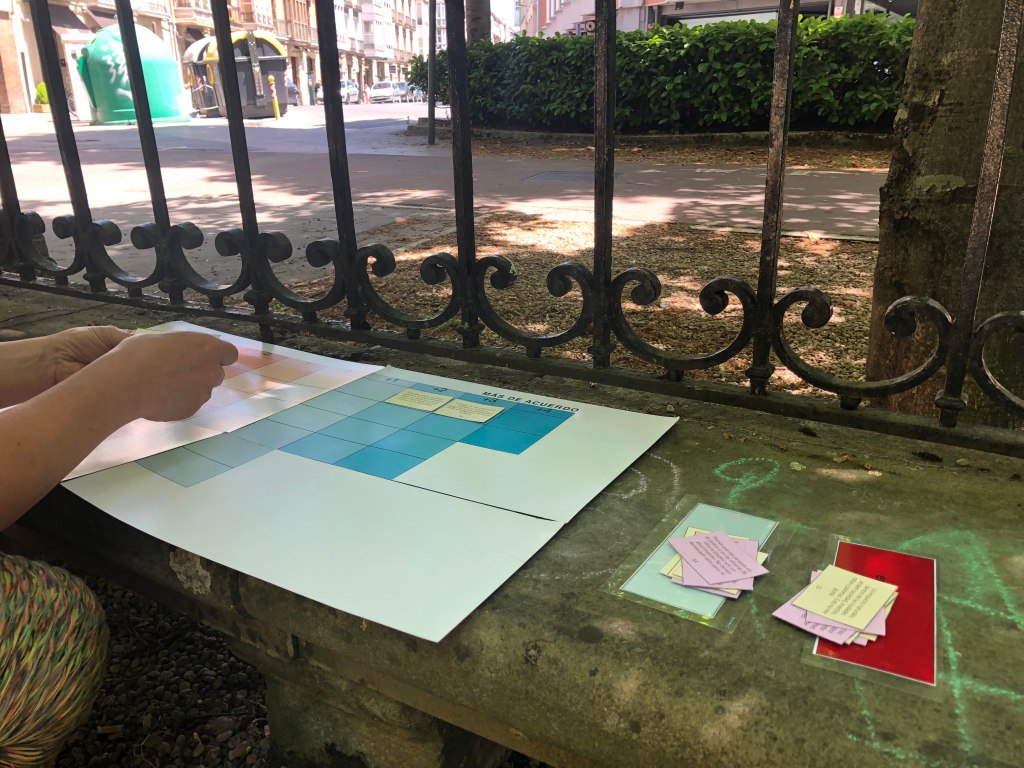

Picture: Julia Neidig

In this paper, we have explored different imaginaries and perspectives surrounding nature hold by urban residents. Or differently said, what values or meanings do urban residents attach to urban nature? Do urban residents align with international policy discourses around the green city that depicts urban nature as universally beneficial? Or do residents connect with nature in a deeply relational way, that is, do they express sentiments of care, stewardship, or belonging with nature, but also with their local community through nature? Or is it the instrumental value of nature, that residents most respond to, such as better air or water quality and the economic benefits associated with urban greening? We sought answers by using a semi-quantitative approach – Q-methodology – in which study participants, urban residents of the Spanish mid-sized city of Vitoria-Gasteiz, ranked specific statements into a forced distribution and found that people relate to nature in complex ways. It is not either the relational or the instrumental value of nature that appeals to people, but a combination of all, based on the people’s diverse memories, places of origins, values systems, and knowledges. This requires intersectional approaches to policymaking in order to be able to provide a just green city.

What is the broader impact of the research? (outside of your specific species/study system)

Picture: Julia Neidig

An increasing body of scholarship across various scientific disciplines is testifying how conceptualization of nature both in theory and (policy) practice are being increasingly associated with an economic growth narrative, that ultimately depicts society above and disconnected from nature. These (mostly Western) narratives leave little space for alternative visions of society-nature relationships and resulting practices that prioritize practices of care for nature and for the community through nature. In this context, the IPBES in its 2022 values assessment has called for nature-positive policymaking that is more inclusive of the plural ontologies and epistemologies emphasizing a plurality of values prevalent in the specific context. With this study, we hence aimed to contribute to this transdisciplinary debate through an empirical study that brings together different conceptual strands, such as ecological economics, value pluralism, and urban planning, by also pinpointing to policy implications of our findings.

Did you have any problems collecting your data?

We conducted this study amid the covid19 pandemic with heavy restrictions of mobility and public space use in Spain. As for the design of the study, that included interaction with study participants, we had to collect our data in safe and public open spaces and were quite limited in the number of surveys. However, this special context of the health crisis also made the study topic much more important, as Spanish citizens were confined to their home for weeks, without access to nature.

Picture: Julia Neidig

What are the implications of your research for policy or practice?

The way we describe, frame, and conceptualize nature in social discourses has a severe impact on the type of policies, programs and governance processes being implemented on the ground. I conclude from our study on plural values about nature in urban contexts and my broader research, that if we describe nature as universally beneficial without understanding its wider context of where, why, and how these nature framing are being made, we enable policy- and decision-making processes ignoring the possible negative impacts of urban greening programs, such as displacement of vulnerable groups through (green) gentrification or the overrunning of local and alternative forms of knowledge. On the long run, this may generate civic contestation or even rejection of making cities greener, which is indispensable if we talk about urban planning in the context of the climate crisis.

About the author:

How did you get involved in ecology?

I am a Social Scientist by training. My PhD, looking at the imaginaries surrounding a contemporary green city ideal, was driven by the idea to understand the strong interplay between the social and ecological, understanding urban environments as socio-ecological systems, thereby drawing a lot on the disciplines of political ecology and ecological economics. That is, we cannot understand social challenges or inequities without looking at how society, social constructions of nature and concrete ecological processes are interlinked.

Have you continued this research, what’s your current position?

I have finished my PhD in December 2023, and am now a Postdoctoral researcher at the Basque Center for Climate Change in the Horizon Europe project BIOTraCes researching the transformative potential of greening urban schoolyards in the city of Vitoria-Gasteiz. In this project, I’m able to build upon my PhD research, and focus on meanings of nature of actors usually marginalized in urban planning processes, namely children with a focus on the co-production of diverse nature’s meaning with the broader educational community.

One piece of advice for someone in your field…

Embrace inter- and transdisciplinary and don’t try to put yourself in one scientific box!