Figure designed by A. Simler-Williamson.

By Matthew A. Williamson, Lael Parrott, Neil H. Carter, and Adam T. Ford.

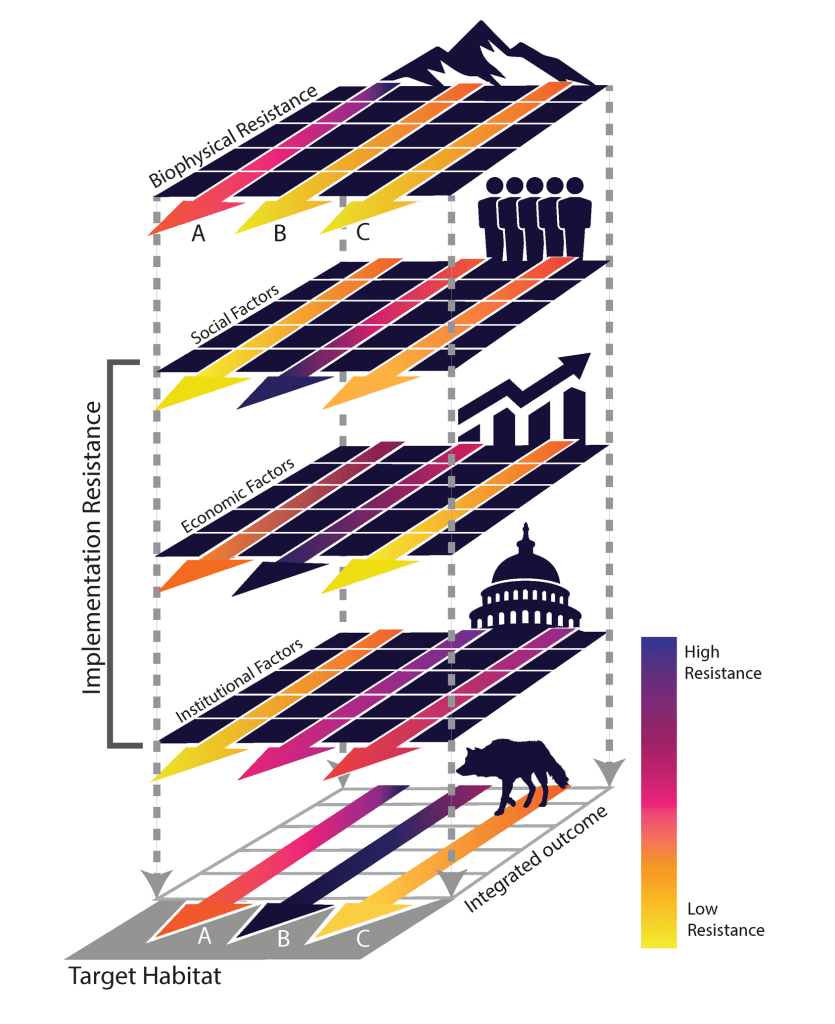

Conserving the ability for species to move across landscapes to access habitat, find mates, and avoid the effects of changing land use or climate (i.e., connectivity) requires identifying pathways that species will traverse and designing interventions that are supported by people that live in those places. Designing connectivity conservation strategies with people in mind necessitates an approach capable of integrating social and ecological dimensions in ways that facilitate scenario testing and actionable decision making. We introduce a framework for integrating optimal movement pathways through a biophysical landscape with the sociopolitical costs associated with conserving those pathways. We argue this approach will lead to connectivity conservation institutions that better align with the interests, values, and needs of people while also addressing the spatial, temporal, and functional characteristics of species movement.

Our paper introduces the idea of implementation resistance, a spatially explicit estimate of the socio-political ‘costs’ a conservation practitioner may face in trying to move from connectivity planning to action. We used a variety of available datasets to demonstrate how implementation resistance surfaces could be constructed to anticipate conservation strategies for the gray wolf (Canis lupus) in the central Rocky Mountains in the United States. Our approach allows for evaluation of trade-offs between ecological objectives and socio-political expedience. We also compared the potential effectiveness of different policy changes to highlight the fact that the effectiveness of any connectivity conservation intervention is highly dependent on the spatial configuration of existing institutions both with respect to the ecological needs of the species and the objectives of surrounding land managers.

We imagine our approach can help identify key social ‘pinch points’ in achieving broader connectivity conservation objectives. By targeting investment in incentives, collaboration, and institutional development in these high-resistance locations we can build social overpasses to overcome persistent barriers to conservation. These “social overpasses” may be as important for maintaining a species’ ability to access habitats, find mates, or avoid climate impacts as much-publicized physical overpasses that help wildlife cross roads.